When I started in this business about 40 years ago (did I just say 40 years – how did that happen?) there were very few auctions of significant collections of Canadian folk art. In 1994, The Sutherland/Amit auction in Bowmanville, Ontario was the first time I recalled a major collection hitting the market and we (being me and my wife Jeanine, my partner in life and business) decided to attend.

We brought along all the cash we could find in our accounts and the couch pillows, hoping to score as much good folk art as possible. By then we’d proved to ourselves that our first love, Canadian folk art, was not only important to us, but also to enough other people that it could be the main focus of our enterprise. Our hope was to snag a few significant pieces while also catching some of the lesser, but equally commercial pieces that ‘fell through the cracks’ and thus presented a good return on investment.

‘One of the greatest benefits of a life flogging antiques and folk art is the people you meet and the friendships you develop.’

Occasionally, another collection would be offered, most often by auctioneer Tim Potter, and we would attend each one, eager to buy pieces that rarely, if ever hit the market. It continues to amaze when on rare occasion you’re able to participate in the dispersal of a great ‘life’s worth’ of collecting.

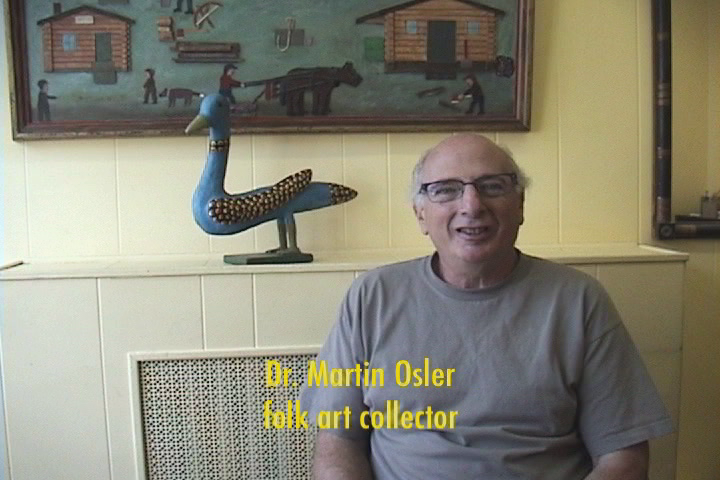

In Miller and Miller’s upcoming Canadiana & Folk Art auction Oct. 8, 2022, items of great importance are being offered from three distinguished collectors: Marty Osler, Susan Murray and Jim Fleming. Over the years, I’ve not only had the pleasure of selling to all of them, but have also come to count them as good friends. One of the greatest benefits of a life flogging antiques and folk art is the people you meet and the friendships you develop.

Of these three, we first met Marty Osler during our earliest days of turning up every Sunday at the Harbourfront Antique market. Marty always felt like a ‘player’, often arriving with an entourage, and he was a tough negotiator between jokes and friendly banter. We kept it friendly, but we often found ourselves stuck within $5 of a deal with neither one of us backing down. Once when I was feeling cranky and had had enough I told him to take off and leave me alone, that I just couldn’t argue over a few bucks anymore. I then felt bad as I liked the guy and he was a good customer. I was happy when he came back and gave me the amount I was asking, explaining “don’t be angry with me over my negotiation. It’s just the way I’m built. If we go out to dinner I’m happy to pick up the bill, but when it comes to buying I have to negotiate to the last penny.” I accepted this and always looked forward to seeing Marty. Later, he would join me at the Shadfly Folk Art Gallery and Antiques in Port Dover, Ontario where I was always amazed at his knowledge and ability to collect pieces I could only imagine. I realized seeing his two previous auctions with Miller & Miller that he was right all along with his seemingly high prices. Everyone who knows him misses his presence at shows and sales, and we miss his visits to our home in Port Dover which usually ended with a trip to the local Chinese buffet.

‘An otherwise unsuccessful show can change completely if you meet that one good customer.’

I met Susan Murray at an otherwise relatively dismal show I once did in Bracebridge, Ontario. It was a well-organized show, it’s just that very few were interested in my offerings. But an otherwise unsuccessful show can change completely if you meet that one good customer. Susan had just bought a cottage in the region and after buying several pieces, explained that along with the cottage she had decided to collect Canadian folk art. She became one of my best customers. Although you wouldn’t imagine it from her friendly and casual demeanor, Susan was a star lobbyist with her own business employing several professionals in three cities. She said it was rare when she could find the time to go to a show or sale, but if I could find the time to bring pieces to her house before she had to start her work day, she would make it worth my while. I was happy to give this arrangement a try in spite of the fact that I had to leave the house at 6 a.m. to be in Toronto for our 8:30 appointment. But good to her word, she would often buy all, or most of what I brought her. We built a close friendship – and her exceptional collection over the years.

‘I remember sharing a place in Lennoxville where if you dropped a pencil it would roll down to the other end of the room. It was beside a river and we were a bit worried we might end up there.’

Jim and Ilona Fleming arrived on our radar sometime in the late ‘90s, as customers with a very good eye, combined with a high level of motivation to expand their collection. Jim was always friendly and fair, but with a determination and intelligence he’d honed as a politician and put to good use acquiring what he wanted. Lovely, friendly people, we soon enjoyed getting to know each other over reciprocal dinners and visits. Once they got into the business it was always fun to meet up at shows and we particularly enjoyed the get-togethers at the end of the day. These are truly some of the best memories we have of the business. For a while, Jim and I would even share a booth and accommodation at some of the shows, such as North Hatley and Lennoxville, both in Quebec. Because the ladies were at home and we were saving on expenses, I remember sharing a place in Lennoxville where if you dropped a pencil it would roll down to the other end of the room. It was beside a river and we were a bit worried we might end up there.

While all these great memories linger with a life of their own, it will soon be time for some incredible pieces from all three collections to pass into new hands, to make new memories, and new friends.

By the mid-nineties we were doing a lot of business with Quebec collector, Pierre Laplante. He was, at the time a very successful dentist, and determined collector of Quebec antiquity and contemporary folk art. A very good fellow who we enjoyed meeting up with every few weeks at his country home, where typically after a good meal and a little wine was consumed we would inevitably end up in his converted machine shed, which was stuffed to the walls with wonderful things, so that I might buy some of what he was prepared to let go of. At the time he was keeping five or six pickers busy full time in an attempt to find him the “all” of the best pieces available. They would bring in full truck loads and he would usually buy everything to get the best price, and assure their dedication. He would sell me all the stuff he didn’t want to keep at very reasonable prices, and that kept me coming back. His appetite was voracious and he rarely said no so there was a lot of stuff arriving. For a couple of years before we both slowed down we did a lot of great business together.

By the mid-nineties we were doing a lot of business with Quebec collector, Pierre Laplante. He was, at the time a very successful dentist, and determined collector of Quebec antiquity and contemporary folk art. A very good fellow who we enjoyed meeting up with every few weeks at his country home, where typically after a good meal and a little wine was consumed we would inevitably end up in his converted machine shed, which was stuffed to the walls with wonderful things, so that I might buy some of what he was prepared to let go of. At the time he was keeping five or six pickers busy full time in an attempt to find him the “all” of the best pieces available. They would bring in full truck loads and he would usually buy everything to get the best price, and assure their dedication. He would sell me all the stuff he didn’t want to keep at very reasonable prices, and that kept me coming back. His appetite was voracious and he rarely said no so there was a lot of stuff arriving. For a couple of years before we both slowed down we did a lot of great business together.

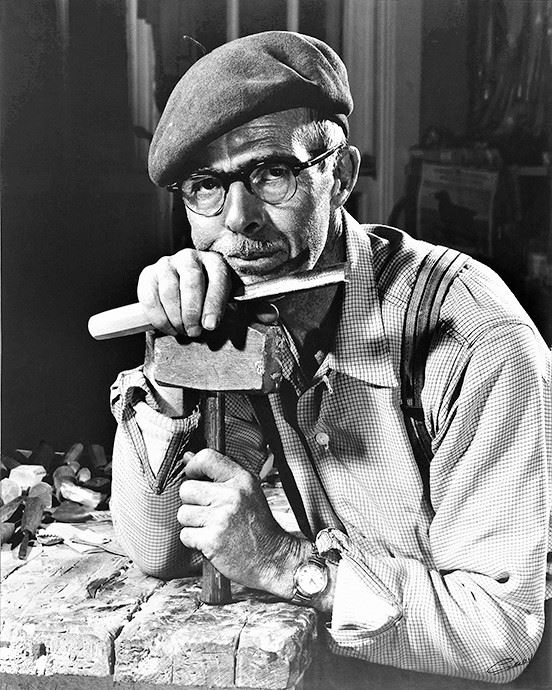

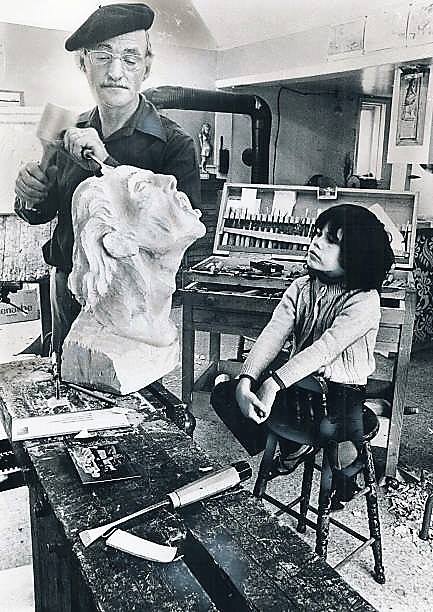

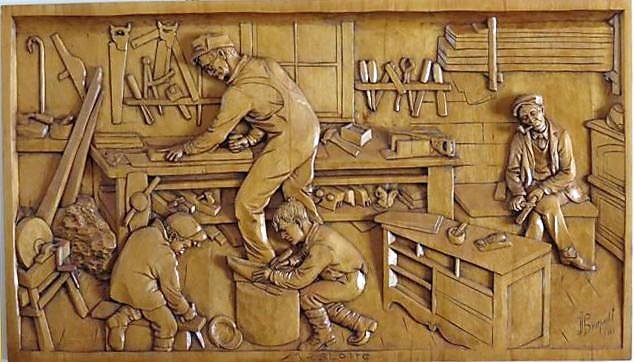

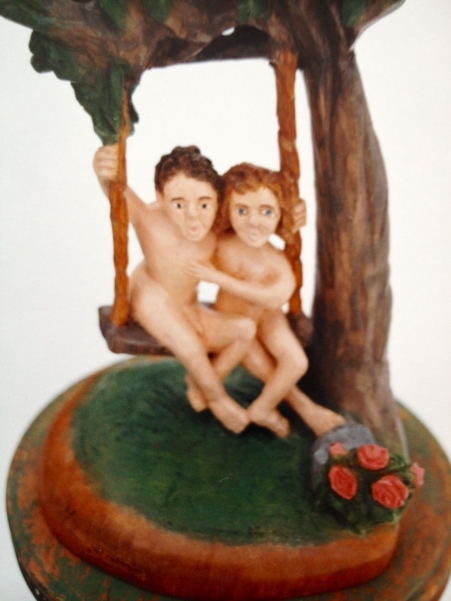

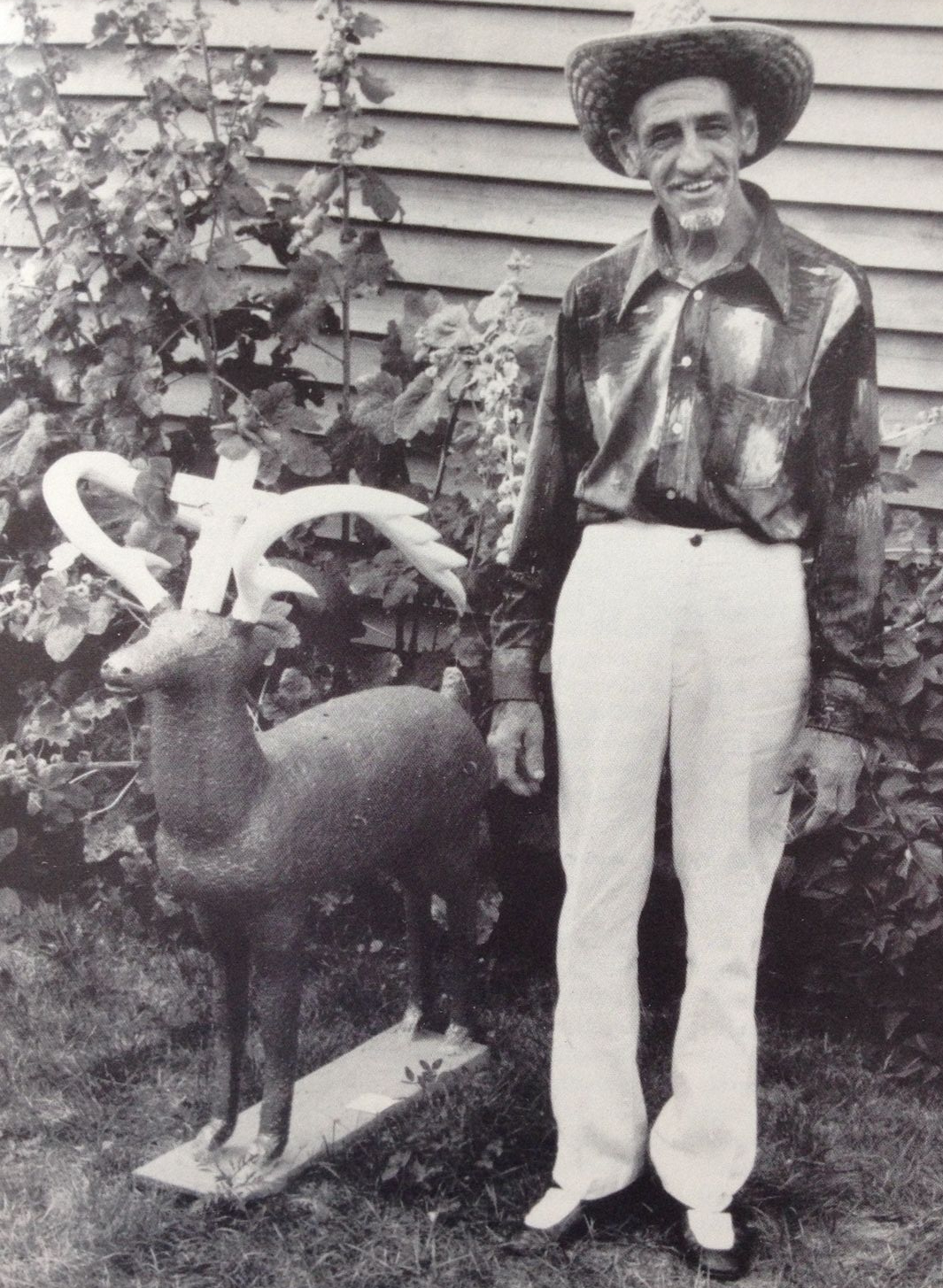

Rene Dandurand’s carvings are worked in one piece from a solid butternut or pine block. Some early works are left bare, showing the grain, but most are painted by his wife Julienne, an excellent colourist, after lengthy consideration of suitable colours. Although Dandurand’s children supplied him with a full set of carving chisels, he prefers the familiarity of his two or three ordinary old knives.

Rene Dandurand’s carvings are worked in one piece from a solid butternut or pine block. Some early works are left bare, showing the grain, but most are painted by his wife Julienne, an excellent colourist, after lengthy consideration of suitable colours. Although Dandurand’s children supplied him with a full set of carving chisels, he prefers the familiarity of his two or three ordinary old knives.

In retrospect, “no slouch when it comes to art” sounds a bit flippant, when I was meaning to suggest that “no slouch” is an understatement. I had and have great respect and admiration for her taste and instincts, and her contributions to the world of folk art. She was also very nice to me when I was a stranger in the midst of the dealers at the Outsider Art Fair in 1996.

In retrospect, “no slouch when it comes to art” sounds a bit flippant, when I was meaning to suggest that “no slouch” is an understatement. I had and have great respect and admiration for her taste and instincts, and her contributions to the world of folk art. She was also very nice to me when I was a stranger in the midst of the dealers at the Outsider Art Fair in 1996. Phyllis was interested in the fact that Billy had created his own “wooden” version of Stonehenge in his back forty, and that he occupied it with many Irish leprechauns, and zodiac figures he had created in cement. She imagined having all the work in her gallery, in a type of recreation of Billie’s world. We excitedly talked on about it a bit more, and we agreed that I would look into it when I got home in terms of interest on Billie’s part, and the logistics of getting all that cement to New York.

Phyllis was interested in the fact that Billy had created his own “wooden” version of Stonehenge in his back forty, and that he occupied it with many Irish leprechauns, and zodiac figures he had created in cement. She imagined having all the work in her gallery, in a type of recreation of Billie’s world. We excitedly talked on about it a bit more, and we agreed that I would look into it when I got home in terms of interest on Billie’s part, and the logistics of getting all that cement to New York.

Gilbert Desrochers was born on May 2, 1926, in Tiny Township. The fifth child in a family of six boys and one girl. His father Thomas owned a farm on the eighteenth concession, overlooking the bluffs of Thunder Bay Beach. He only attended school for two years when his mother died, and he went to work with his father and brothers on the family farm. “I wasn’t much good in school” he recalled. “I didn’t learn much. I went to school only to smoke. And I slept. I was always so tired that I fell asleep. I had no notion about school. I had only work in my head. I figured that work was easier than school.” Our father couldn’t read or write either and said “it’s just as well that you are like me. Come work with me in the woods.” “My father had two hundred sheep, and we took care of them. Also nine cows, three horses, chickens and pigs. In the winter we would cut wood all the time. We didn’t have a power saw so me and Joseph would cut wood all winter. It was a lot of work with cross-cut saws and Swede saws.

Gilbert Desrochers was born on May 2, 1926, in Tiny Township. The fifth child in a family of six boys and one girl. His father Thomas owned a farm on the eighteenth concession, overlooking the bluffs of Thunder Bay Beach. He only attended school for two years when his mother died, and he went to work with his father and brothers on the family farm. “I wasn’t much good in school” he recalled. “I didn’t learn much. I went to school only to smoke. And I slept. I was always so tired that I fell asleep. I had no notion about school. I had only work in my head. I figured that work was easier than school.” Our father couldn’t read or write either and said “it’s just as well that you are like me. Come work with me in the woods.” “My father had two hundred sheep, and we took care of them. Also nine cows, three horses, chickens and pigs. In the winter we would cut wood all the time. We didn’t have a power saw so me and Joseph would cut wood all winter. It was a lot of work with cross-cut saws and Swede saws.

I was busy right from the get go until about 2:30 when I told the last man in line that yes, I could go out to the parking lot to look at a chess table he had brought in, but right after that I had to go and eat a sandwich, as I was starting to fade. A lot of what I saw was fairly common turn of the century prints in late Victorian frames which is one of those “let them down easy” moments. Some ask, “Are you sure it’s not a painting. I was always told it was a painting”, and so you point out the company name and date written in tiny print right down along the bottom, and that usually convinces them. You also look at a lot of chairs, I suppose because everybody’s got some kicking around and they are easy to bring in. Lots of looking at large furniture on cell-phones. Some of it amazing stuff, but if they are looking to unload it, it’s hard to think of who you might suggest is dealing in massive, walnut Jacques and Hayes sideboards. Still, you give them what’s called the fair market value, that being the highest value that would be paid between a knowledgeable buyer and seller in a fair and uncontrolled market. This is the figure you use for insurance purposes. You then explain that this figure is often higher than you could hope to receive selling it to a dealer. Dealers needing to make money, and eat, etc. It’s amazing how many people do not “get” this concept until it’s introduced to them.

I was busy right from the get go until about 2:30 when I told the last man in line that yes, I could go out to the parking lot to look at a chess table he had brought in, but right after that I had to go and eat a sandwich, as I was starting to fade. A lot of what I saw was fairly common turn of the century prints in late Victorian frames which is one of those “let them down easy” moments. Some ask, “Are you sure it’s not a painting. I was always told it was a painting”, and so you point out the company name and date written in tiny print right down along the bottom, and that usually convinces them. You also look at a lot of chairs, I suppose because everybody’s got some kicking around and they are easy to bring in. Lots of looking at large furniture on cell-phones. Some of it amazing stuff, but if they are looking to unload it, it’s hard to think of who you might suggest is dealing in massive, walnut Jacques and Hayes sideboards. Still, you give them what’s called the fair market value, that being the highest value that would be paid between a knowledgeable buyer and seller in a fair and uncontrolled market. This is the figure you use for insurance purposes. You then explain that this figure is often higher than you could hope to receive selling it to a dealer. Dealers needing to make money, and eat, etc. It’s amazing how many people do not “get” this concept until it’s introduced to them. Shortly after an interesting well-dressed woman showed me a few items on her phone. When she hit the shot of the early 19th century folk painted door from Nova Scotia I just about wet myself. Holy Mackerel, talk about hitting all the buttons. This thing has it all. Every one of the four panels, front and back is decorated with scenes of ships at sea, forests, and other maritime features, with every molding decorated with geometrics in lovely colours, etc. You could see the surface was untouched and magnificent. A stellar piece of museum quality. I was able to recreate one of those classic “roadshow” moments. “Well, a normal door of this period would be worth a few hundred dollars, but I would place a fair market value of $15,000 on this door. Gasps and giggles all around. She was of course delighted. I asked her what she paid for it and she told me she paid a lot for it 35 years ago. The $750 she forked out just about blew her marriage but she felt she had to have it. She said the husband is long gone. I told her she was better off with the door. We laughed and had a good time for a couple of minutes and then it was time to move on. Her parting comment was that she had not yet found a place for it in her new home but that she was going home to do so, and fetch it out of the basement.

Shortly after an interesting well-dressed woman showed me a few items on her phone. When she hit the shot of the early 19th century folk painted door from Nova Scotia I just about wet myself. Holy Mackerel, talk about hitting all the buttons. This thing has it all. Every one of the four panels, front and back is decorated with scenes of ships at sea, forests, and other maritime features, with every molding decorated with geometrics in lovely colours, etc. You could see the surface was untouched and magnificent. A stellar piece of museum quality. I was able to recreate one of those classic “roadshow” moments. “Well, a normal door of this period would be worth a few hundred dollars, but I would place a fair market value of $15,000 on this door. Gasps and giggles all around. She was of course delighted. I asked her what she paid for it and she told me she paid a lot for it 35 years ago. The $750 she forked out just about blew her marriage but she felt she had to have it. She said the husband is long gone. I told her she was better off with the door. We laughed and had a good time for a couple of minutes and then it was time to move on. Her parting comment was that she had not yet found a place for it in her new home but that she was going home to do so, and fetch it out of the basement.